Kalamazoo Medieval Congress Blog: Thursday 7:30

Thursday, May 11, 2017 - 17:48

All the participants have connections to the University of York. The session is organized to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the program there.

Thursday 7:30: Reflecting on Gender and Medieval Studies

· Sponsor: Centre for Medieval Studies, Univ. of York

· Organizer: Craig Taylor, Univ. of York

· Presider: Craig Taylor

From Women to Men, and Back Again

Katherine J. Lewis, Univ. of Huddersfield

Paper title refers to her field of study which began with women’s history and then moved to concepts of kingship. Legend of St. Katherine contrasting concepts of kingship’s relationship to concepts of masculinity. Is kingship related to power over others, or does self-mastery make one greater? Thus the “frail” woman S. Kathering stands higher than King Maxentius who challenged her. This highlights the performative nature of gender, rather than biological determinism, as women saints, especially, can perform “masculine” virtues and rise above their biological origins.

Katherine’s life was often included in general textual collections, alongside romances, which may reflect its use as an example to women of a desirable but transgressive life. But what its reception might be by male readers? What appeal would it have to men in modeling the performance of piety? S. Katherine is depicted by Caxton as a model of kingship, her father’s heir and ruling her household as such. This is more a model of masculine rule than a model for a woman’s stewardship over a household. Caxton’s text explicitly offers her as an example to men of such governance.

We get a summary of the contents of a particular manuscript collection that includes a Life of S. Katherine. Including an inserted indenture for one James Fytt, written on a blank page, recording his agreement with the Guild of S. Margaret regarding a bequest. There is a suggestion that he may have commissioned the manuscript. The Life of S. Katherine in this text also includes a detailed description of how she rules her household after her father’s death.

This is an example of an urban household, depicted similarly to that of the man who we presume was the manuscript’s original owner. The characteristics are not simply the sort of extreme piety and asceticim we often see in lives of female saints, but a very practical and worldly concern for the welfare (including spiritual welfare) of those who depended on her. She gives charity, but retains sufficient good to run the house. She does not withdraw, but concerns herself with the behavior of those under her authority. Self-mastery is a significant component of the virtues she represents.

Katherine’s ability to rule is associated with her ability to perform these “masculine” virtues, and in turn she becomes a model of those virtues for men. She is considered not to have “transgressed” her gender but to have “transcended” it. Even so, her biography provides a model to women that such a transcendence is possible and available.

From Romances to Bromances: Studies in Masculinity at York and Beyond

Rachel E. Moss, Corpus Christi College, Univ. of Oxford

Paper is looking at the field of masculinity studies and its future. Begins with the (modern) Brock Turner rape incident to raise the issue of elitism and masculine privilege at prominent universities. This is a reminder that the issues in medieval studies are still active today, and the role of academics of addressing issues of sexism (among other isms) in academia and research.

The problem of “how can we believe a ‘good guy’ might be a rapist” she raises the probability that Geoffrey Chaucer was a rapist, and resistance to that consideration from those who admire his writing. Moss chose to study masculinity in the middle ages, not to side-step consideration of women, but to focus on it. The study of patriarchy, not simply as a socio-political system but as an on-going social system, which informs her current study of homosociality. It is a system that, by privileging male-male social relationships, supported and maintained patriarchal systems. One of her topics is the function (and necessity) of rape as a tool of that maintenance.

Homosocial bonds such as those in institutions such as sports clubs and fraternities, as well as close friendships of (straight) men christened “bromances”, are an essential element of rape culture, wherein men invite their male comrades to participate vicariously in their sexual assaults as a bonding function. The male witnesses are more important than the female “conquests”.

What does this have to do with medieval studies? Privileged medieval men participated in a culture where the threat of violence against women was an essential component of their social bonds with each other. For example, Chaucer’s The Reeve’s Tale, in which two clerks punish a greedy miller by a combination of raping his daughter, and tricking the miller’s wife into having sex with one of them by deception. The two clerks treat this as an appropriate social victory against the miller. The story is played for broad comedy, which requires a male gaze to accomplish.

Those some scholars try to find nuance in the story, it is inescapable that the clerks (and Chaucer the author, and the presumed reader) consider it appropriate and natural to punish a man by sexually assaulting “his” women. The clerks overtly consider that it will make a good story to tell later, one must assume to their male peers. This type of storytelling and audience appreciation are a performance primarily intended as in-group bonding. These performances establish the boundaries of appropriate masculine behavior. The fate of the miller’s wife and daughter after the end of the story is considered irrelevant. It isn’t part of the story.

How do we recognize how the reflex to defend this type of historic content as a type of rape culture while still teaching historic content in its own context? Recognize that the canon is not neutral and that the selection of what it taught not only reinforces sexist understandings of history, but also is a “story we tell each other” that reinforces sexism in the academy by promoting this sort of homosocial bonding among academics and thus excluding marginalized participants.

From Romance to Administrative History: New Perspectives on Queenship in Late Medieval England

Lisa Benz, Univ. of York

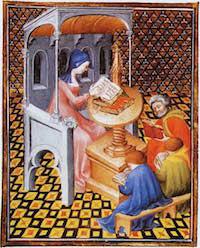

She will discuss how she came to work on the topic of her thesis on queenship, having begun with an interest in Arthurian romance. What did it mean to be a queen in practice? Textual sources include ceremonies, didactic literature, histories, biographies. Model images of queens in these sources were influential in creating an ideal of queenship.

“Mirrors for princes” and similar texts were prevalent in the 14th century, but few touched on the subject of queenship. A few 15th c. texts address the question, but most do not. Christine de Pizan addresses queenship in her woman-centered texts, but not in her general works.

Vitae and chronicles retrospectively portray queens as paragons of virtue, to set them up as models for behavior. The “spin” put on their lives was more important than the factual details of their lives, and stock tropes might be assigned to them for this purpose.

Queens in romances supply a different model: often the calumniated queen or the guilty queen. Queens may depict sovreignty, but it is typically resolved by her marriage to a man. The calumniated queen (myserious pregnancy) typically shifts to a focus on the adventures of her resulting son, including his redemption of his mother. The guilty queen typically takes a lover and conspires to kill the king, requiring punishment for the resolution.

Chronicles of actual queens often depict the same event in different ways depending on the particular chronicler’s didactic purpose. Hagiographies similarly cannot be consider factual as their religious purpose was more important than their descriptive one. And romances can’t be considered factual at all.

These texts show the competing ideas and expectations, but the actual historic women had more complex lives. In the early 20th century, historians of queenship moved away from the simple biographical narratives and began addressing the evidence of non-narrative sources, such as accounts and administrative records. Economic and structural studies of the queen’s household (especially as it became distinct form the king’s household) provide a less biased look. But there was still a preference for focusing on queens with “good stories” Studies of Iberian queens have been particularly rich in data for looking at these contrasting approaches to the research.

Much summing up that I can’t keep up with. Plus some specific examples of types of evidence from administrative documents.

Major category: