Kalamazoo Medieval Congress Blog: Friday 1:30

Friday, May 12, 2017 - 11:47

Session 233: Dress and Textiles II: Real and Unreal

- Sponsor: DISTAFF (Discussion, Interpretation, and Study of Textile Arts, Fabrics, and Fashion)

- Organizer: Robin Netherton, DISTAFF

- Presider: Gale R. Owen-Crocker, Univ. of Manchester

A Change of Face, or, A Man in an Otter Suit

M. A. Nordtorp-Madson, Univ. of St. Thomas, Minnesota

[Speaker was unfortunately not able to attend.]

The Real Unreal: Chrétien de Troyes’s Fashioning of Erec and Enide

Monica L. Wright, Univ. of Louisiana–Lafayette

Chrétien de Troyes shows his familiarity with contemporary fashion in the extensive and detailed descriptions of clothing in his romances. But not all clothing in the stories is meant to be realistic. In some cases the specifics are symbolic and “unreal”.

Structurally, there are two sequences, beginning and ending with a gift of clothing that is described in detail. The first begins with a gift of armor from Enide’s father to Erec. Erec’s clothing is rich and describes actual garments, though he does not wear armor, which lack is symbolically important. Enide, in contrast, has beome impoverished, which is refelcted in the simplicity of her initial garments: a linen mantle over a threadbare linen chemise, but lacking the expected bliaut which would be an expected part of court wear. The sequence ends with a gift of clothing from the queen to Enide, who previously has remained in her poor clothing. The description of Enide’s clothing gift is long and detailed, again reflecting actual contemporary fashions.

The second sequence is when the two venture out on adventures in the midst of conflict between them. Enide is instructed to wear her finest clothes--those the queen gave her--which will attract the attention of Erec’s adversaries in this section.. The central part of this sequence includes a number of gifts of clothing that Erec hands out to resolve problems along the way. This sequence concludes with the couple reunited and invested to rule the realm of Enide’s late father. There is a long description of Erec’s coronation mantle with its elaborate embroidered decorations. Although these might seem improbable in theme, they are similar in detail and them in existing royal mantles from the general era.

Some details of the mantle, however, are deliberately fantastic, such as the work being attributed to fairies, and the description of the strange and colorful legendary beasts that provided the fur lining. Or are they so strange? In other manuscripts, some furs are described as coming from the orient, and Write notes some furred creatures native to Asia such as the Giant Malabar Squirrel and a type of monkey whose multi-colored fur is consistent with the description in Erec.

(Summary tying the clothing descriptions and dynamics in with the contemporary social and political landscape.)

“Monstrous Men of Fashion”: Striped Costume in a Danish Church Wall Painting

John Block Friedman, Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, The Ohio State Univ.

During 15th c “ungodly creatures” began to be depicted in Dnaish church paintings. This paper concerns such depictions of “monsters” derived from Pliney’s writings, but shown wearing fashionable “Landsknechte” style clothing in the early 16th century in a church at Raaby. There is an anecdotal story of how such works might have been commissioned. Figures at Raaby include:

- dog-headed man

- one-eyed man with long ears

- sciopode (with umbrella-like foot over his head) & prominent erection

- horned man with long nose

Possiby connected with these are similar figures in churches near Aarhus, wearing similarly fashionable clothing of other styles.

Whey are the monsters clothed at all? And in familiar garments? The contrast between humans and monsters suggests that monsters should be depicted naked or in the styles of foreign lands.

Two features make the Raaby onsters unusual. The carefully depicted garments are a turning point in the depiction of monsters. But they also reflect an antagonistic reaction to the landsknechte mercenaries via a hostile association of them with monsters. The mercenaries were specifically exempted from sumtuary laws and encourated to use clothing display as a cohesive strategy. And their low pay encouraged rapacious behavior in the wake of battles, hence their bad reputation.

The visual significance of the Landsknechte clothing style resulted in plentiful visual documentation, but early depictions are often hostile.

[There is a general discussion of fashionable changes in the doublet in the 14-16th century, especially with regard to social critique of them.]

The Raaby sciopode is not wearing landsknechte styles but rather a more academic robe. Thus contrasting the intellectual and bestial qualities.

Vivid striping on the figures’ hose and codpieces draws attention to a novel aspect of the style, where the lower limbs are increasingly displayed. By the early 16th century, German art often associated striped clothing with outrageous figures and tormenters, as in crucifixion, flagellation, and St. Sebastian scenes. We’re now looking at alterpieces and other paintings from Germany and Austria.

Thus the dressing of the Danish monsters creates an association between unhuman monsters and the violent and rapacious behavior associated with landsknechtes, as well as with violent sexuality.

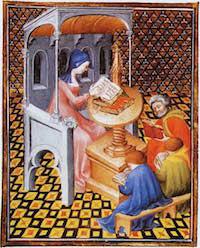

Tall Hats, Scrolling Brims, and the Byzantine Scholar in Late Medieval European Painting

Joyce Kubiski, Western Michigan Univ.

In the 15th century a particular hat style begins appearing in European art from the east moving to the west. It seems to be a fantastical item used to reprsent Jews and other foreigners. But garments of this sort were not entirely inventions, but relied in origin on an actual association with a foreign garment, though often fantastically elaborated later.

This “hat with a scrolling brim” has a round crown with a knob on top, and a bifurcated upturned brim.

It may date to contacts with Byzantine diplomats traveling to western European capitals looking for assistance. Western representations of Byzantine dress are more common than Byzantine ones due to later destruction of art during political and religious upheavals. Everyday dress is particularly difficult to research for this reason.

Although this hat style had clear symbolic meaning in western art, it isn’t clear what it may have symbolized in its original cultures of origin. It was used to symbolize a “benign” foreigner, or ancient Greek philosophers and the like. Later it morphed into a more general sign of “otherness”, not necessarily benign, and might be applied to foreigners from other places than the east.

Italian artist Pisanello (early 15th c) created portraits of the Byzantine emperor John VIII Palaeologus, and this is the earliest appearance in western art of the hat with the scrolling brim (HwtSB). This item has a tall rounded crown with a knob and a brim in two parts, the front one elongaged and pointed, turned up, though not rolled as the later depictions show. Pisanello’s portrait was designated the only “official” image of the emperor and thus became strongly associated as an icon. Possibly for this reason, although the emperor clearly had other garments and caps, descriptions of him usually include this hat.

Official depictions of the emperor in Byzantine art never show him in this hat style, though textual descriptions indicate less formal everyday wear than the official Byzantine portrait styles.

Other sketches by Pisanello of the emperor show a number of other hat styles and clothing. Five different hat designs are show, not including the iconic style eveually used for the official portrait. Some of these other hats show up in images of the Byzantine court included on a set of bronze doors commissioned for Saint Peter’s at the same time. This is a design much closer to the iconic HwtSB, with a high rounded crown, with a tall brim turned up and split at the sides, with the edges scrolled in various directions.

Possible Byzantine visual evidence includes a 14th c image of a saint wearing a stiff tall hat with a split brim, and a Serbian version of the Alexander romance where Alexander and his court wear a tall-crowned, tall-brimmed hat, split at the sides and scrolling.

The later medieval European depictions are modified significantly from these early images but have a clear structural connection, as well as a strong symbolic association, first with Byzantine and Greek individuals, later with eastern foreigners, and then with foreigners in general. The connection via Pisanello’s art supports a conclusion that this is a real garment with actual Byzantine associations, despite its later abstraction as an artistic signifier.

Major category: